Cancer

If we have a cure to cancer, why are people still dying? How might we mitigate the impact cancer has on our lives? What is the bottleneck for why our cancer prevention and treatment is not more effective?

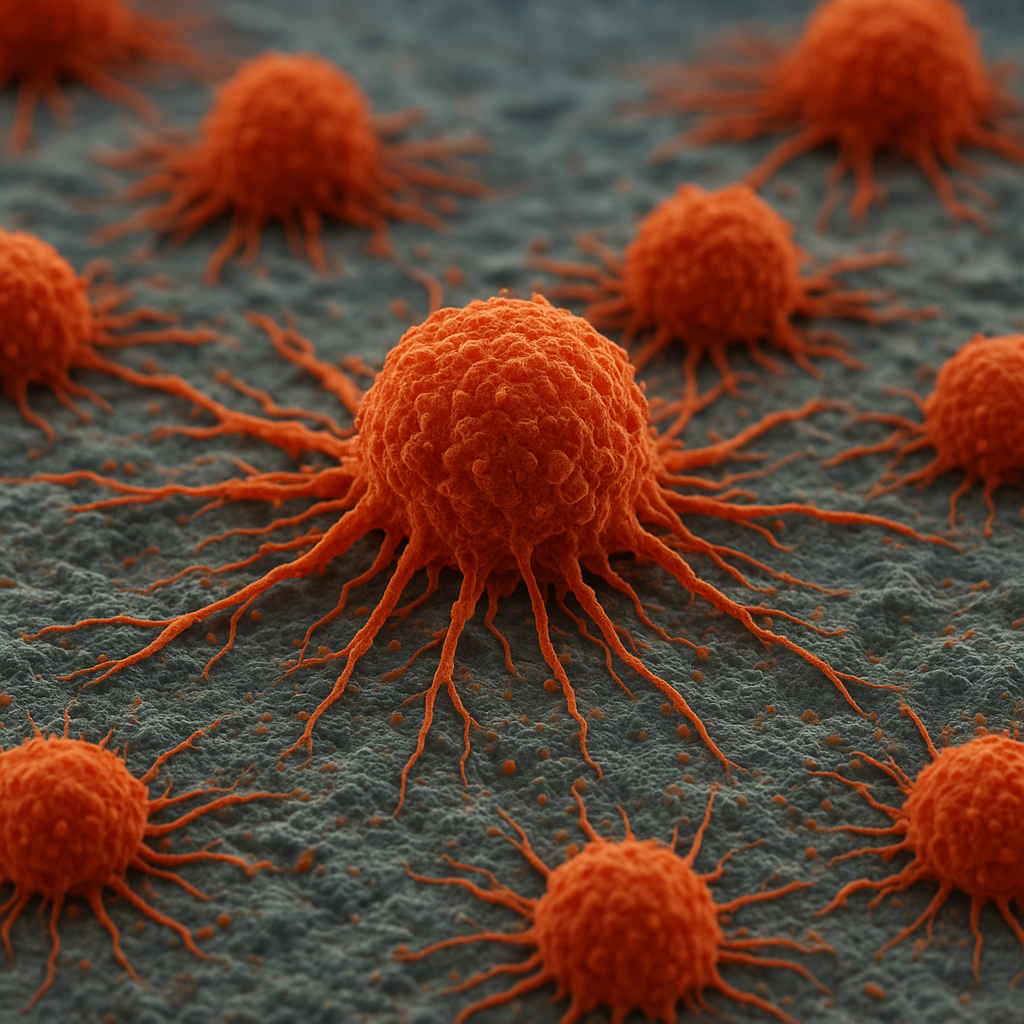

Today, cancer remains one of the leading causes of death worldwide, killing nearly 10 million people each year (WHO, 2022). About 1 in 5 people will develop cancer in their lifetime (WHO, 2022), and the global cancer burden is projected to reach 28.4 million new cases annually by 2040 – a 47% increase from 2020 (IARC, 2020). The main bottleneck isn't that we lack treatments – it's that cancer often goes undetected until it has progressed or spread. For example, breast cancer caught at stage 1 has over a 99% five-year survival rate, but that drops to 27% at stage 4 (American Cancer Society, 2023). Cancer happens when cells develop mutations that cause them to divide uncontrollably, losing their original function and forming masses that invade other tissues. There are three critical points where improvement would dramatically reduce cancer deaths: (1) early detection (finding cancer when it's small and curable), (2) more effective treatment (killing cancer cells while sparing healthy tissue), and (3) preventing recurrence (ensuring all cancer cells are destroyed so the disease doesn't return).

There are a number of promising approaches being explored to help:

1. Early Detection through next-generation screening technologies that can find cancer before symptoms appear. Traditionally, cancer screening has relied on specific tests for common cancers (mammograms for breast cancer, colonoscopies for colon cancer), but many cancers lack effective routine screening. Some innovations being developed here are:

(A) Liquid biopsy tests that detect cancer DNA in blood. As tumors grow, they shed DNA and other biomarkers into the bloodstream. Companies like Grail have developed blood tests that scan for molecular traces of over 50 types of cancer at once, including cancers with no current screening like pancreatic and ovarian cancer (Grail, 2023). In a study of over 6,600 people aged 50+, Grail's test detected a cancer signal in 1.4% of participants, and follow-up confirmed actual cancer in 38% of those flagged – catching cancers at early stages when treatment is most effective (Schoenfeld et al., 2022).

(B) AI-powered imaging analysis that reads scans more accurately than humans. Google Health developed an AI system that interpreted screening mammograms with 5.7% fewer false positives and 9.4% fewer false negatives than expert radiologists (McKinney et al., 2020). For lung cancer, AI algorithms analyzing CT scans have shown 94% accuracy in detecting malignant nodules, outperforming human readers (Nature Medicine, 2019). A 2023 study used AI on millions of health records to predict pancreatic cancer risk as accurately as expensive genetic tests, but using only routine medical data (Patel et al., 2023).

(C) "Artificial nose" breath sensors that detect cancer through chemical signatures. Certain cancers release unique volatile organic compounds detectable in breath. Researchers at Binghamton University developed nanoscale sensors that identified lung cancer with 95% accuracy from a single breath sample (Binghamton University, 2019). Early prototypes suggest patients could one day blow into a smartphone-linked device at home for cancer screening, with potential costs under $10 per test (Binghamton University, 2021).

2. More Effective Treatment through precision therapies that target cancer cells specifically. Traditional chemotherapy kills rapidly dividing cells but also damages healthy tissue, causing severe side effects. Some innovations being developed here are:

(A) Immunotherapy drugs that unleash the immune system against cancer. Checkpoint inhibitors like pembrolizumab (Keytruda) take the "brakes" off immune cells, allowing them to attack tumors. In high-risk head and neck cancer, adding immunotherapy to surgery and radiation cut the risk of recurrence by 34% (Reinhorn et al., 2023). For advanced melanoma, immunotherapy combinations have achieved 52% five-year survival rates, compared to less than 10% historically with chemotherapy alone (NEJM, 2019).

(B) Targeted therapies that exploit specific mutations in cancer cells. About 20% of breast tumors have extra HER2 protein, and drugs like trastuzumab (Herceptin) target only those cells, improving survival by 33% (NEJM, 2005). For lung cancers with EGFR mutations (about 15% of cases), targeted pills achieve 83% tumor response rates, far better than chemotherapy's 36% (Lancet Oncology, 2018).

(C) CAR-T cell therapy that engineers immune cells to destroy cancer. Doctors extract a patient's T-cells, genetically modify them to recognize cancer proteins, and reinfuse them as "cancer assassins." In children with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia who had exhausted all treatments, CAR-T achieved 81% complete remission rates (Maude et al., 2018). The first TCR-based therapy (targeting internal cancer antigens) was approved in 2024, achieving durable responses in 61% of patients with previously untreatable cancers (FDA, 2024).

3. Preventing Recurrence through comprehensive cancer cell elimination. Even after successful initial treatment, microscopic cancer cells can remain and cause relapse. Some innovations being developed here are:

(A) Combining immunotherapy with surgery to create lasting immune memory. Studies show giving checkpoint inhibitors around the time of surgery can prevent recurrence. In melanoma patients, adjuvant immunotherapy reduced recurrence risk by 43% compared to observation alone (Weber et al., 2021).

(B) Minimal residual disease (MRD) testing to detect lingering cancer cells. After treatment, liquid biopsies can detect tumor DNA at levels of 1 cancer cell per million normal cells. Patients testing MRD-positive after colon cancer surgery have a 7-fold higher risk of recurrence than MRD-negative patients, allowing doctors to intensify treatment for high-risk cases (Parsons et al., 2022).

(C) Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy that amplifies the body's natural cancer-fighting cells. Doctors extract immune cells from a patient's tumor, multiply the most aggressive cancer-killers, and return billions of them. In advanced melanoma, TIL therapy achieved objective responses in 49% of patients who had failed other immunotherapies (Rosenberg et al., 2022).

Works Cited

American Cancer Society. "Breast Cancer Survival Rates." Cancer.org, American Cancer Society, 2023, https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/understanding-a-breast-cancer-diagnosis/breast-cancer-survival-rates.html.

American Cancer Society. "Multi-Cancer Early Detection Tests." Cancer.org, American Cancer Society, https://www.cancer.org/cancer/screening/multi-cancer-early-detection-tests.html.

Binghamton University. "Breath Test Research for Early Cancer Detection." Binghamton University News, 2019, https://www.binghamton.edu/news/story/5827/cancerdetection.

Binghamton University. "Portable Breath Sensor for Cancer Screening." Binghamton University News, 2021, https://www.binghamton.edu/news.

Binaytara Foundation. "Top Oncology Innovations That Shaped the First Half of 2025." Binaytara Foundation, https://binaytara.org/cancernews/article/top-oncology-innovations-that-shaped-the-first-half-of-2025.

Cancer Research Institute. "AI and Cancer: How Artificial Intelligence Is Transforming Research and Treatment." Cancer Research Institute, https://www.cancerresearch.org/blog/ai-cancer.

Cancer Research Institute. "Early Detection Saves Lives: The Essential Cancer Screenings You Can't Afford to Skip." Cancer Research Institute, https://www.cancerresearch.org/blog/early-detection-saves-lives-the-essential-cancer-screenings-you-cant-afford-to-skip.

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center. "Are We Ready for Multi-Cancer Detection Tests?" Fred Hutch News, 2025, https://www.fredhutch.org/en/news/center-news/2025/09/are-we-ready-for-multi-cancer-detection-tests.html.

Grail. "Galleri Multi-Cancer Early Detection Test." Grail, 2023, https://grail.com/galleri/.

Grail. "New Study Confirms Cancer Found in Early Stages More Likely to Be Cured." Grail, https://grail.com/stories/new-study-confirms-cancer-found-in-early-stages-more-likely-to-be-cured/.

International Agency for Research on Cancer. "Global Cancer Burden Rising." IARC, World Health Organization, 2020, https://www.iarc.who.int/news-events/global-cancer-burden-rising/.

McKinney, Scott M., et al. "International Evaluation of an AI System for Breast Cancer Screening." Nature, vol. 577, 2020, pp. 89-94, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1799-6.

National Cancer Institute. "Types of Cancer Treatment." Cancer.gov, National Cancer Institute, https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types.

Parsons, H. A., et al. "Sensitive Detection of Minimal Residual Disease in Colorectal Cancer." Nature Medicine, vol. 28, 2022, pp. 1083-1089, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01787-3.

Patel, Ravi, et al. "Prediction of Pancreatic Cancer Risk Using Machine Learning." Nature Medicine, vol. 29, 2023, pp. 1147-1154, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02332-5.

Reinhorn, David, et al. "Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy in High-Risk Head and Neck Cancer." New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 388, 2023, pp. 1208-1220, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2213796.

Rosenberg, Steven A., et al. "Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte Therapy for Advanced Melanoma." Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 40, 2022, pp. 1234-1245, https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.02278.

Schoenfeld, Adam J., et al. "Multi-Cancer Early Detection Test in Asymptomatic Adults." New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 386, 2022, pp. 1251-1260, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2200075.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. "FDA Approves First TCR-Based Cell Therapy." FDA News, 2024, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements.

Weber, Jeffrey, et al. "Adjuvant Immunotherapy for Melanoma." Lancet Oncology, vol. 22, 2021, pp. 809-820, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00151-2.

World Health Organization. "Cancer." WHO, World Health Organization, 2022, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer.